What is a Stormwater Utility?

Governor Lamont's Climate Bill, House Bill 6441, passed in July of 2021, allows for Connecticut Municipalities to be able to implement Stormwater Utilities. Stormwater utilities are fees which generate direct, stable funding for stormwater management. They are often labelled as a fair and equitable source of funding as the fee is not based on property tax, but on impervious cover, allowing all properties, even tax-exempt properties, to contribute to the stormwater fund. On the boxes below, you can find a breakdown of the essentials of House Bill 6441:

Who can Implement a Stormwater Utility?

Previously, only New London was granted the power to implement a stormwater authority as a pilot program. Now, any municipality within the state can implement one.

Purpose of the Utility

Within the Bill, the purposes of a stormwater utility is broken down into 6 parts. The purpose of the utility is to:

- Develop a stormwater management program (including, but not limited to):

- For construction and post-construction site stormwater runoff control, including control detention and prevention of runoff from development sites

- For the control and abatement of stormwater pollution from existing land uses and the detection and elimination of connections to the stormwater system which threaten public health, welfare, or the environment

- Provide public education and outreach, as well as establish procedures for public participation

- Provide for the administration of the utility

- Establish the geographic boundaries of the stormwater utility district

- Recommend to the legislative body the imposition of a fee on the interests in real property as the revenues to be used in carrying out any powers

- The utility may plan, layout, acquire, construct, reconstruct, repair, maintain, supervise, and manage stormwater control systems

Establishing a Fee

Fees approved by the legislation can be levied on property owners for the purposes of the utility. When establishing the fee, the utility fee shall take into consideration (but is not limited to) impervious surfaces on properties which generate stormwater runoff and land use types which may generate higher or lower concentrations of stormwater pollution.

Fees may be reduced or deferred for farm, forest, or open space land. Fees are only allowed to be levied on the parts of these which contain impervious surfaces which generate stormwater runoff.

Stormwater Utility Budgets

When establishing a budget, the utility must include (but is not limited to) specific programs to be undertaken during the fiscal year, the projected expenditures for the programs for the fiscal year, and the amount of the fee or fees planned to be levied to pay for the expenditures. The budget of the utility must be presented to legislation of the municipality annually. The aggregate amount of the fees proposed for a fiscal year must not exceed the aggregate amount of the projected expenditures for that fiscal year. The amount of the fees can be less, but not greater than what is proposed by the authority.

Unpaid Fees

Any fee that is not paid for in full on or before the 30th day after the date of which payment was due shall bear interest at such rates and in such a manner as provided for delinquent taxes. Any unpaid fee or portion unpaid, and interest due on the fee, shall constitute a lien on the property of the property owner to be recorded and released in the manner provided for property tax liens. Any person aggrieved by the stormwater utility has the same rights and remedies for an appeal and relief as is provided for taxpayers who are aggrieved by the doings of the assessors or board of assessment appeals.

Enforcement

The stormwater utility can adopt municipal regulation to implement the stormwater management program.

Collaboration on Stormwater Utilities

The stormwater utility can (subject to the commissioner’s approval) enter into contract with any municipal or regional entity to accomplish the purposes of the stormwater utility.

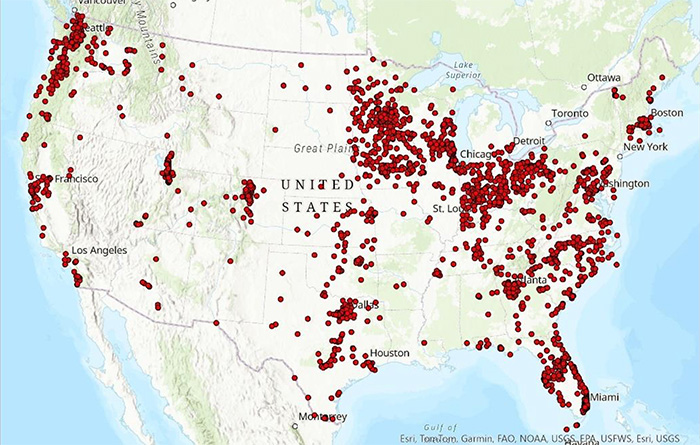

Who has one?

Over 2,100 stormwater utilities have been implemented within 42 states across the country. Implementation of these utilities is not dependent on geographic location or population size. Implementation of these utilities has ranged from Los Angeles, California, the second largest city in the country with a population of over 4 million to Indian Creek Village, Florida, with a population of 88 people (Western Kentucky University). The average monthly single family resident fee is $6.19. Connecticut is currently home to two stormwater utilities: one in New London and one in New Britain.

The Capitol Region Council of Governments was recently awarded grant funding through the CT DEEP Climate Resiliency Fund for a regional stormwater utility feasibility study. Feasibility studies are the first step to evaluating if a stormwater utility would be a good fit for the area in question. For more information, visit their website: https://crcog.org/regional-planning-and-development/environment-energy/regional-stormwater-authority-study/

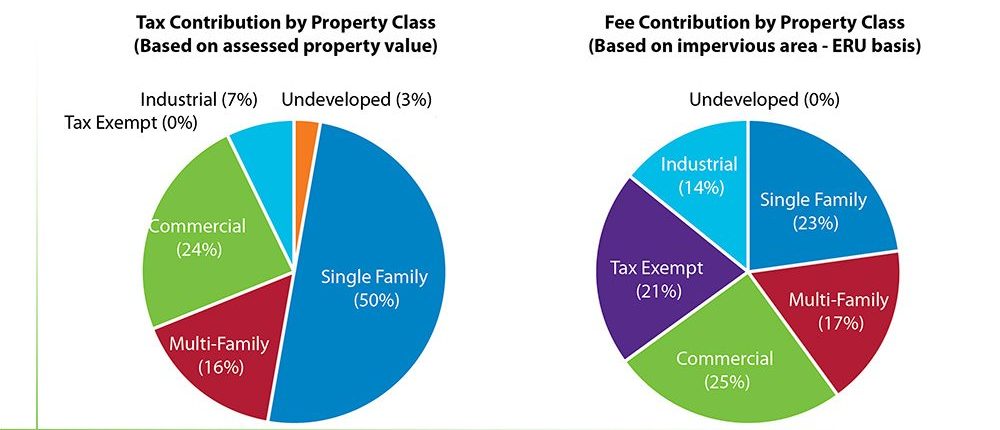

Property Tax vs. User Based Fee

This image from CDM Smith's work in Lynchburg, VA (utility established in 2012) demonstrates the comparison of taxed-based funding vs. user fee funding. Stormwater utility fees are designed to be fair and equitable, distributing the fee based on the user and how much they contribute to the stormwater system rather than their property value. This allows for tax-exempt, commercial, and industrial properties to contribute their fair share of funding. Stormwater management funding from a property tax within Lynchburg would have resulted in a poorly distributed fee, with residents in single family and multi-family housing making up over 60% of the funding contribution. On the other hand, with a user based ERU fee, residents only make up 40% of the funding contribution. The majority of the funding in this case comes from commercial, industrial, and tax-exempt properties.

It should be noted that every municipality will result in different makeups of funding contributions depending on the tax base, tax exempt parcels, and impervious area. However, this example from Lynchburg, VA demonstrates the far more equitable distribution of fees provided by stormwater utilities when compared to a property tax. For more information on fee systems, visit out Fee Structures page.

Stormwater Utilities in Action

There are numerous benefits which can be provided by stormwater utilities as the funding can be put directly towards towns’ necessary projects without any need to compete with other projects for money from a general fund. To see stormwater utilities in action, click on each tab below. You can also find more information on our Stormwater Utility and MS4 Compliance factsheet.

Aging Infrastructure and Flooding Mitigation

Often, the most reported concern of residents is aging infrastructure. In a 2024 Stormwater Utility survey, 61% of respondents reported that aging infrastructure was one of the highest ranked stormwater management issues. Having funds on hand to address this concern has benefits for both the town and residents. Up to date infrastructure means a lower potential for flooding and illicit discharges and puts residents at ease seeing their money directly benefiting them and the town they live in.

Augusta, Georgia has been plagued with aging infrastructure and excessive flooding. While its rich history adds to the value of the city, the out-of-date drainage system has led to both physical and economic setbacks. With an estimated $240 million backlog of stormwater infrastructure repairs, the city desperately needed a more direct way to fund the imperative upgrades. Previously, stormwater funding had been gathered from a combination of a general fund and a Special Purpose Local Options Sales Tax fund. Because the funding source was unreliable and had to be shared amongst other projects, the city could only afford six stormwater crews to man the various jobs required to improve drainage and stay in compliance with the MS4 permit. With the implementation of a stormwater utility in 2016, Augusta generated separate stormwater funds to be put towards doubling the amount of stormwater crews, rehab and repair of stormwater infrastructure, street sweeping, and catch basin cleaning to prevent flooding incidents. The city has already created a plan to take on 13 new priority projects addressing drainage improvements and flood hazard mitigation.

Green Stormwater Infrastructure

In Raleigh, North Carolina, the funds collected from their stormwater utility has led to a massive green infrastructure push. In the Fall of 2021, the city constructed a 1,700 sq. ft. bioretention area to collect and absorb surrounding stormwater runoff. The six trees and more than 750 plants spread throughout the bioretention area are expected to keep six pounds of nitrogen and 109 pounds of suspended solids from entering waterways every year.

On top of the direct use of funding, stormwater utilities can be a great way to incentivize homeowners and private property owners to participate in DCIA disconnection. Because the utility fee is based on the amount of impervious cover on a property, residents could have the opportunity to reduce their fee by reducing their total impervious cover. This can be done with a credit or discount system. Portland, Oregon offers stormwater credits for all property types - industrial, commercial, multi-family, single-family, and more. For residential properties, residents can receive fee discounts of up to 100% for properly managing rooftop stormwater runoff. The city provided examples of simple green infrastructure homeowners can use to disconnect rooftop DCIA, such as dry wells and french drains, lawns and rain gardens, rain barrels, and eco-roofs. By offering these discounts, residents may be more likely to disconnect their own homes, adding to the total percentage of disconnected DCIA towns need each year to be compliant with the permit.

Water Quality

The stormwater utility in South Burlington, Vermont, established in 2005, has been dedicated towards improving water quality within the area. The city has increased water quality monitoring, with active streamflow and precipitation monitoring stations in their impaired streams reporting real time data.

The stormwater utility in South Burlington, Vermont, established in 2005, has been dedicated towards improving water quality within the area. The city has increased water quality monitoring, with active streamflow and precipitation monitoring stations in their impaired streams reporting real time data.

The fund has also improved water quality through the removal of illicit discharges. In 2006, the city discovered a sanitary sewer pipe which had been accidentally connected to the stormwater drainage pipes and discharging directly into local waterways since 1994. Funding from the utility was used to dig up and reconnect the pipe to the correct system. At the same time, they were able to conduct further investigation to ensure no other nearby illicit connections were present. Since then, monitoring results have shown a reduction in pollutant levels at this outfall.

The City of Bellingham, Washington took measures to address the excess phosphorous and bacteria entering the nearby Lake Whatcom. Their stormwater utility allowed for the planting of native vegetation and phosphorous-removing filter cartridges within nearby drainage areas help improve the water quality of the lake and meet their Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL) standard.

Find out more about stormwater utilities:

For citation purposes: University of Connecticut’s Center for Land Use Education and Research. (March 14, 2022). Stormwater Utilities. https://nemo.uconn.edu/stormwater-utilities/